The final part of this essay moves still further backwards in time, to the very first moving-image projection – within a space created especially for spectators – of sequences of walking, running and intersecting human figures. The projection took place at another Exposition event, in Chicago: the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, for which the moving-image innovator Eadweard Muybridge constructed a building – part performance exhibition-space, part proto-cinematic space – in order to project his sequences of figures in movement. As with the projection environment of Hijikata’s filmed performance The Birth, Muybridge’s experiment is one for which almost all traces of the projection-space have been lost. Only two photographs still exist of the facade of Muybridge’s building, the ‘Zoopraxographical Hall,’ and none of the interior of the space itself.

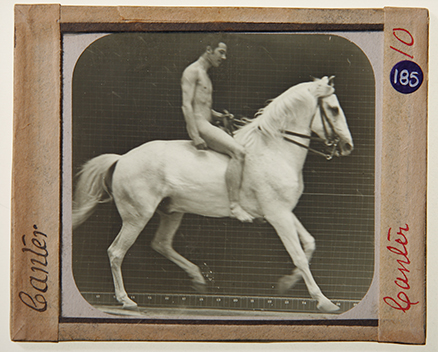

Muybridge was the first moving-image innovator to envisage a specially constructed space, to be entered by spectators, who – in conditions of darkness – would then experience moving-image sequential-projections of human figures performing acts of walking, of encountering one another, even embracing one another: an experience intimately close to that of the spectators of Lovers, a century later. Muybridge’s work as an inventor focused on the performative gestures and movements of the human body, especially in situations of crisis and malfunction; he experimented with the ways in which those gestures connected with moving images, in the form of projections that could surround their spectators, and thereby instigate unprecedented visions and sensations. He began experimenting with immersive, 360-degree image-environments as early as 1878, fifteen years before his Chicago projections. At that time, his focus had been on urban space, rather than on human figures. He assembled large-format photographic panoramas of San Francisco, and installed them in such a way, within an art-gallery space, that they surrounded their viewers, inducing a sense of topographic disorientation. During the same period, he also began experimenting with moving-image projection for spectators, using sequences of images transferred onto glass discs; he constructed a projector, which he called the ‘Zoopraxiscope,’ to animate those images. In 1884, he was commissioned by the University of Pennsylvania, in Philadelphia, to use multiple, high-speed cameras to capture images of human bodies, as well as animals, in sequential movement. Over a span of three years, he created more than twenty thousand sequences, including those of figures who pivot and turn rapidly, as also occurs in the Lovers installation. Muybridge directed and choreographed his human models specifically as performers, who undertook pre-set acts of performance, rather than isolated gestures or improvisations. The filmmaker Hollis Frampton commented on the excessive nature of Muybridge’s project and its axis in acute repetition: “Quite simply, what occasioned Muybridge’s obsession? What need drove him, beyond a reasonable limit of dozens or even hundreds of sequences, to make them by thousands? … Time seems, sometimes, to stop, to be suspended in tableaux disjunct from change and flux. Most human beings experience, at one time or another, moments of intense passion during which perception seems vividly arrested: erotic rapture, or the extremes of rage and terror came to mind.”6

In his specially constructed projection-space at the Chicago Exposition in 1893, Muybridge projected his Philadelphia sequences, along with newly created sequences, from glass discs. He had been planning a large-scale projection tour – extending across Japan, India and Australia – but abandoned it, in order to participate in the Chicago Exposition, which appeared to offer him an unprecedented arena to demonstrate his innovations. Since no pre-existing building constructed uniquely for the projection of moving-images preceded it, Muybridge had to imagine that space entirely for himself. His plans for the building’s facade indicate that he envisaged a spectacular form, with classical columns, inspired in part by ancient Greek and Roman theatre architecture; the building stands in splendid isolation in his plans, without the presence of other, competing Exposition attractions. His projection-space was around fifty by eighty feet in dimension, constructed from brick, iron and wood. When Muybridge describes the building, in promotional material prepared for the Exposition, he gives the impression that it had appeared almost magically or spontaneously, without human intervention. He refers to himself in the third person: “He delayed his Far Occidental expedition and returned to Chicago to find a commodious theater erected for this special purpose on the grounds of the Exposition, to which the name of Zoopraxographical Hall had been given.”7 Almost nothing is known about the interior space of Muybridge’s building; in the absence of any writings on the subject by Muybridge himself, or any eye-witness accounts, it is simply not known whether he projected his sequences immersively, around the interior walls of the space. Since he possessed only one projector, he would have needed to rotate it, in mid-projection, through revolutions around the space, in order to do so. All that is known with certainty is that Muybridge himself stood alongside his projection surfaces (or screens), as a corporeal and vocal presence, and narrated his sequences of figures-in-movement to his audiences. It is also certain, from attendance figures for the Exposition’s many attractions, that the project – in financial terms – was a disastrous failure; Muybridge drew only very few spectators into his projection space.

As with the Osaka Expo ’70, the Chicago Exposition was an immense undertaking, lasting for six months. Its total attendance was around 27 million – around half that of Expo ’70 – but the number of exhibitors with whom Muybridge was competing was huge: 65,422. Every exhibitor in Chicago had a new technology or a new spectacle of some kind to display, often with far greater promotional resources and within much more extravagant buildings than Muybridge. In that architectural and promotional context, Muybridge’s projection-space generated only a negligible presence, despite its extraordinary ambition and innovation as a seminal site for moving-image projection, in the form of an experimental laboratory for future visual technologies. Only halfway through the duration of the Chicago Exposition, Muybridge’s projection-space was closed and demolished, and razed without trace; its location was then rapidly re-occupied by another exhibitor and a new building – the ‘Pompeii Theater and Panorama’ – containing a painted panorama of Pompeii during its destruction by the volcanic eruption of Mount Vesuvius. As with the Osaka site of Expo ’70, that of the Chicago Exposition would also rapidly disappear, first abandoned, then largely destroyed by a fire, several months after its closure. Muybridge undertook no further experiments in moving-image projection after his experience in Chicago; he scaled down his activities, returned to his home-town of Kingston-on-Thames in England, and bequeathed his entire personal archive of projectors, images and documents to the town’s library on his death in 1904.

The traces and survival of immersive moving-image experimentation, around projected bodies in performative movement – from Muybridge’s 1893 projections of human-figure sequences, through the 1970 Astrorama immersive projections of Hijikata’s choreographic work, to Teiji Furuhashi’s 1994 Lovers installation, and extending into the present moment – are often precarious, their status subject to erasure or reactivation in new, contrary forms. They depend upon memories and documentation which are flawed, partial, or even non-existent. Archives of performance projections often comprise fragmented detritus, fissured by time, and imprinted by disparate approaches to documentation, rather than source materials for acts of flawless reconstitution. Such archives themselves possess engulfing spectatorial demands, and precipitate transits in flux across the histories and spaces of performance. They also indicate that whatever appears to be a contemporary, immediate new-media technology conceived for incorporation within performance can, very rapidly, appear obsolete and vanish – but then resurge aberrantly in a new manifestation, often with original and compelling imperatives for its future spectators. All resilient performance-traces demand attention, even when their resilience is the result of accident or chance. In exploring the dynamics of innovations in performance cultures, and the preoccupations and intentions of their creators – such as those which drove Furuhashi’s Lovers – it is always essential to view together the event of performance and its surviving moving-image documentation, together with the pivotal role of the human body which intimately interweaves them.