This essay focuses on Lovers (1994) the first – and last – moving-image installation work of Teiji Furuhashi, viewed within the framework of the histories of immersive moving-image projection environments involving human figures in performative movement. Lovers possesses an intricate rapport with previous experiments in immersive moving-image projection in relation to performance and choreography, and in turn illuminates the intimate interweaving of performance with other media, such as film and digital forms. Alongside Lovers, this essay will examine a film-projection experiment, The Birth, shown at the Japan World Exposition festival in Osaka (the event now better known as ‘Expo ’70’) involving the work of the ankoku butoh choreographer, Tatsumi Hijikata. The final part of this essay will extend back to 1893 – one hundred and one years before the first installation of Lovers – to examine the originating event for all projections of moving-images within specially-designed, enclosed spatial environments: the project of the English moving-image innovator, Eadweard Muybridge, to create the first-ever space for the projection of moving-images to public audiences, through the construction of his ‘Zoopraxographical Hall’ at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago – a project which, like Lovers, shows images of naked human figures, walking, in sequential movement, and in intersections and encounters. The aim of this essay is not to situate Lovers within a static lineage of immersive moving-image projections, but rather to show that the preoccupations driving such experiments form enduring and transformational ones, that manifest themselves in very distinctive and dynamic ways that can challenge and overturn their audiences’ preconceptions of the corporeal and ocular dimensions of performance.

In 1998, I had the experience, as a spectator, of being present within the spectral moving-image environment of Lovers. Developed in collaboration between Furuhashi and an innovative digital arts agency operating in Tokyo, Canon ArtLab, Lovers was installed within a range of arts-museum spaces internationally in the years following its first appearance, when it was shown at a gallery space for performance and moving-image experiments, the Hillside Plaza, in Tokyo, from 23 September to 3 October 1994. The Hillside Plaza was used, during the period 1990 to 2001, for many other moving-image installations, including a retrospective of the work of the well-known Japanese filmmaker Takahiko Iimura; that space still exists, but is now used to host corporate events and receptions. The first installation of Lovers belongs to a particular moment in the development of Japanese digital art, from the early 1990s on, in which technology corporations such as Canon and NTT actively sponsored work, or provided environments for performance-focused experiments with emergent digital moving-image and virtual-reality technologies, often working closely with digital artists and performers to provide them with funding and technical support which were otherwise scarce. By 1998, NTT had opened a large-scale arts museum of contemporary digital technology, the InterCommunication Center, in Tokyo’s Shinjuku district, and Lovers was also exhibited there, as part of the exhibition Possible Futures. My own experience of being a spectator of Lovers was at its installation within another Tokyo venue, Spiral Hall, in 1998, three years after the death of Furuhashi, and also at the end of that distinctive period of arts-curation that encompassed performance and experimental moving-image technology. The Canon ArtLab would dissolve in acrimony, after a curatorial dispute in 2001, and the NTT InterCommunication Center also experienced severe operational difficulties in the same era, though it still exists. Digital arts curation then became subject to entirely different imperatives across the following decade, the 2000s, and into the current moment.

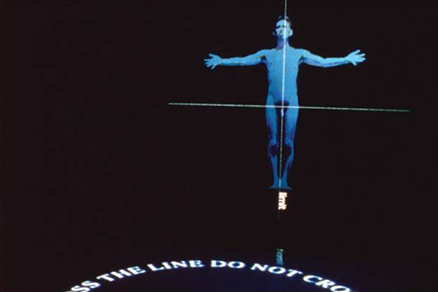

In an interview from 1995, Furuhashi evokes the theme of Lovers in the context of its projection technologies: “In conventional terminology, the piece is called a multi-media installation. It uses lifesize images of nine naked performers which circle the room round the viewer; five laser discs; and seven video projectors. It deals with the theme of contemporary love in an ultra-romantic way.”1 Two of the most significant elements of the design of the installation are, firstly, that its projected sequences surround or immerse its spectator (intimately so, since Lovers was usually exhibited within relatively constrained confines), and secondly, that the spectator’s body and eyes actively participate in determining the projection of walking and intersecting figures. A short promotional film by the Canon ArtLab, made at the time of the Hillside Plaza installation, emphasises this second aspect of the work: “Sensors in the centre of the space are activated by the visitors’ presence, triggering words and images to move and react on the wall. Sensors that dot the ceiling are triggered to project messages down on to the floor, creating boundaries.”2

As a spectator of Lovers, in 1998 at Spiral Hall in Tokyo – within that soundscaped environment of slow-motion bodies that walked, ran, and embraced while simultaneously evanescing – I was struck by the sense of a volatile process of infiltration between the projected and spectatorial bodies in that space, especially during the moments at which, as the spectator approached those projected bodies, they abruptly vanished, and another figure, that of Furuhashi, moved towards the spectator, before falling backwards. I noted among the English-language texts that appeared within the projections one that read: “Do not cross the line,” and another: “A jailbreak across ordinary fields is harder than over walls and wire fences.” That second text brought to mind – within the projection-space of Lovers – the experience of Jean Genet (a great hero of transvestite and transsexual culture in Japan, from the 1960s onwards), during his incarceration as a child, in the 1920s, at the French rural prison of Mettray (a prison surrounded by open fields, rather than by walls). In one of his texts, Genet wrote: “One of the finest inventions of the [Penal] Colony of Mettray was to have known not to put a wall around it – it’s much more difficult to escape when you have to cross a bed of flowers.”3 Genet’s final book is titled Prisoner of Love – the same title as a love-song associated with James Brown. The preoccupation in Lovers with ‘prisoners of love’ and ‘love-songs’ interconnects that work with dumb type’s S/N performance of the same era, with its focus on the potential forms of future love-songs. That ‘love-song’ preoccupation materialises in the S/N performance in the form of a song performed by Barbra Streisand, People who need people, as well as inciting the spectator’s eye – and body – to traverse boundaries. Genet filmed the eyes of prisoners and wardens, peering through spyholes, in his 1950 film, with the same title, Un Chant d’Amour, or A Love Song. Fearing that a needle, directed from the far side of the cell-door, will pierce his eye and blind him, the character of the warden in that film is still compelled by sexual desire for his prisoners to look through that aperture. What he sees are not prisoners in misery, but instead, prisoners who are engaged in a choreographed sexual frenzy – they dance wildly, or are masturbating – and two prisoners communicate with each other via the wall between two cells, through which a hole has been drilled, and cigarette smoke is blown from mouth to mouth through that aperture. A future ‘love-song’ may involve an opening-up of flesh, in the cutting of two wrists, and the mixing of blood, as in S/N, or else the piercing of an aperture, as with that of a film-camera lens, in conjuring into existence the intersecting and intercrossing bodies of Lovers, which then intimately surround their spectators.

The contemporary status of Lovers is a potentially precarious one; it must be projected, in order to exist. It holds sparse traces, as a future ‘love-song,’ since it is now exhibited and projected with relative infrequency, at least in contrast to its international prominence in the second half of the 1990s. But since it was acquired as an ‘art work’ by several museum collections in that era, it therefore exists multiply, in editions of its constituent materials and sequences, and the corporeal presences they hold, ready for revivification. Its originating materials may also be stored archivally, but archives of projection-experiments are notably fragile ones that risk undergoing transmutations and disintegration. The current interstitial status of Lovers connects with an alternative title (or sub-title) sometimes used for its 1990s projections: Dying Pictures, Living Pictures.

- T. Furuhashi, interviewed by Carol Lutfy, Tokyo Journal’s TJWeb, Sep. 1995, web, renfield.net/tj/9509/converse.html, last accessed: 20 Feb. 2014. [↩]

- In 2014, the short promotional film, which would have been distributed by the Canon ArtLab in the mid-1990s in video-cassette format to prospective art-museum exhibitors of Furuhashi’s art-work, was freely accessible on youtube.com: www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZAaYEZN7EwI. [↩]

- J. Genet, L’Ennemi Déclaré, Paris: Gallimard, 1991, p. 223. [↩]