On stage, the audience sees a private room: a rug, a chair, a table with personal items: laptop, mobile phone, books, magazines, CDs, notebooks, pens, an ashtray … on the floor, a TV set and a stereo. Diyaa Yamout, the central character in 33 rpm and a few seconds (2012), the latest production by Lina Saneh and Rabih Mroué, seems to have gone out briefly to fetch cigarettes or to meet friends. He should be coming back any minute … Or someone else should be coming … After all, someone has to come. But no one does.

33 rpm and a few seconds revolves around the suicide of a young man: Diyaa Yamout is a prominent public figure in Beirut – a theater maker and political activist. The reasons for taking his own life, however, are purely personal or philosophical, as he explains in a suicide note; neither familial, emotional or social problems, nor a political or artistic project are the basis for his action. Nonetheless, his suicide triggers a vivid public debate, which goes far beyond the question of whether it should be considered a public or private act. Why did he take his life at a moment when the revolutions and uprisings of the so-called Arab Spring stirred hopes for change in Lebanon? Would suicide in a moment like this not have to be considered a sign of resignation? In which way, then, could his political project for a secular Lebanon be continued? Yamout does not provide any answers to these questions. Instead, they begin to take on a life of their own: not only his friends, acquaintances and sympathizers, but also religious and political figures from different ‘camps’ take public stands, make claims, speculate, discuss, argue, understand, defend, or instrumentalize his action. The media – ranging from social networks to major news and television stations – become the sites of the debate.

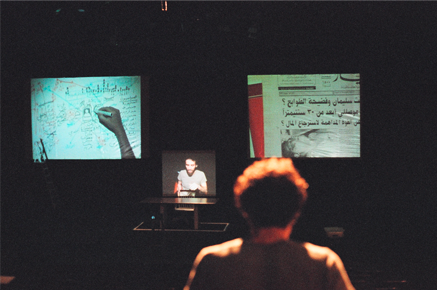

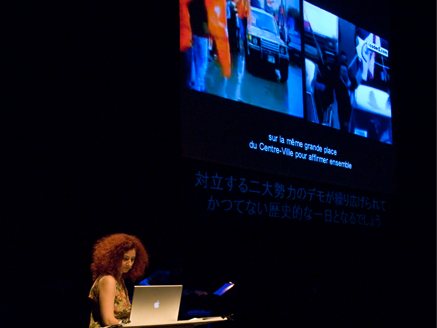

For that reason, the media claim the stage in 33 rpm and a few seconds: just like the public debate that followed Yamout’s suicide, the media that played an important role in his life – Facebook, his mobile phone, answering and fax machine, the TV – take on a life of their own. In quick succession, opinions, messages, and news reports occupy and dominate the stage, many of them projected on a huge screen in the background. Even a power outage that suddenly disrupts this constant stream of images, sounds, text and speech – and in which, for a moment, the theatrical apparatus itself is revealed – becomes insignificant as the machines reboot automatically; everything continues as before. All this time, the stage remains empty.

A stage void of actors. One cannot help but wonder if this piece should still be considered ‘theater.’ Even though broad categorizations like this may be somewhat tedious and surely insufficient, it seems essential to situate 33 rpm and a few seconds in the realm of theater and performance – as Saneh and Mroué suggest. However, this is not just another version of a theater of machines, light, or objects. Nor is the fact that the stage remains filled with media and void of people a mere coincidence. Instead, it is a highly radical artistic statement. Just like in Mroué’s performance Looking for a Missing Employee (2003), the physical absence of the central character is here both subject matter and artistic strategy: 33 rpm and a few seconds renders visible that which usually defies representation – that is, the gap, the absent itself. This juxtaposition of a fundamental absence and the hyper-presence of the various media (which in turn are based on physical absence) results in a compelling and insoluble tension on stage; and it is from this tension that the production draws its critical potential.

In 33 rpm and a few seconds, Saneh and Mroué do not attempt to explore the reasons for the suicide, but rather reconstruct the public reactions it triggered. Within the mediated verbal repartee, political platitudes and power struggles, sectarian and secular rhetoric, social issues and conflicts, and, implicitly, the deep, intractable divisions of the Lebanese society are put on display. This discursive mesh, carefully woven over the course of the performance, reveals the difficulties and limits of the constitutional, yet in practice impossible balancing act between democratic majority rule on the one hand, and the representation of the 18 officially recognized confessional minorities in Lebanon on the other. Like Saneh and Mroué’s production Photo-Romance (2009), 33 rpm and a few seconds subtly shows the consequences of the political stalemate following the ‘Cedar Revolution’ of 2005 – a stalemate which has led to a sequence of paralyzed governments; a stalemate in which the citizens of the revolution soon disappeared into the masses of sectarian political ‘camps.’

The empty stage in 33 rpm and a few seconds, on the other hand, confronts the audience with the death of an individual: ironically, the physical absence of the central character in a space permeated by a multitude of social, political, cultural, and sectarian discourses gives Yamout even more weight. This is especially significant in the context of a society in which the constitution does not grant civil rights to its citizens. In fact, personal status as well as family law of all Lebanese citizens are regulated by religious courts; each individual’s membership in their community of faith is mandated even after death by means of specific religious burial rituals. In her performance Appendix (2007), Saneh also explores these topics and their inherent lines of conflict: she reflects upon the possibility of surgically removing her organs in a series of operations and burning each of them afterwards, in order to gradually remove the body from its societal ties and thus to reappropriate it. Yamout also asked that his body be incinerated after his suicide. He thus repudiated fundamental religious commandments; at the same time, he rejected the ‘fact’ of confessional belonging, which, in Lebanon, is commonly naturalized and considered to be at the core of each citizen’s identity. By taking his own life and demanding that he be cremated, he sought to avoid living on in death – be it as part of a religious community or as a (political) martyr. Yamout may have taken the reasons for his suicide to his grave. The power to interpret them, however, is assumed by those social, political and religious forces he attempted to escape.

Like other works by Saneh and Mroué, 33 rpm and a few seconds is based on actual public events and circumstances. This simple statement – although not false – is also rather problematic, since it suggests an unambiguous relation between an event and its artistic treatment. The boundaries between reality and art, truth and imagination, documentary and fiction, however, are not clearly defined, but fluent and permeable. Saneh and Mroué often explore and employ these ambiguities in their performances. They tend to find their materials in the public sphere of Beirut: historical events (especially from the period of the Lebanese Civil War and its unsettled aftermath) as well as political and social conditions, their medial representations and the public discourses surrounding them are at the heart of their performances. The works deriving from the process of critical exploration are profoundly political: they do not simply represent a specific status quo or political attitude, nor do they propose answers or solutions. Instead, they shake predominant belief systems and deconstruct hegemonic concepts. They reveal socio-political contradictions, lines of conflict, and taboos inherent in (Lebanese) society within the shared space of the theater.