“An armed soldier and a security gate.” If someone asked me to imagine Pakistan, that is what would come to mind.

The reason I decided to go to Pakistan was to be in the middle of a conflict, which I somehow believe will be the center of a 3rd World War. Pakistan, which means “pure land” in Persian, was conceived as a Muslim utopia, a land that was supposed to fulfill the prophet Mohammad’s promise of equality and brotherhood. However, the reality of contemporary Pakistan offers different prospects. Today, we see a postcolonial society busy with ethnic strife, the rise of radicalism, and constantly under the anonymous threat of American drones.

But this is not the Pakistan I wanted to go see. That Pakistan I can see in Berlin, thanks to Wikipedia and the Internet. If you have a toy capable of spelling “www,” actually traveling to the “Orient” is unnecessary. In any case, I went to Pakistan not to reaffirm the information I already had, or to run around following my Lonely Planet. The reason I went to Pakistan was to distance myself from consumerist life in the West by encountering its opposite. The camera kept running. I placed myself in a new role, playing a character as he visits a “pre-civilized” world. I envisioned myself walking on the ruins of a future war, experiencing the apocalypse, now.

That sounds ridiculous, right? But let’s be honest: what else brings an Iranian living in Germany to Pakistan? The woman working for the Turkish airline at Berlin’s Tegel airport didn’t want to issue my boarding pass because she thought my ticket to Karachi was a joke.

Once in Pakistan, though, I ended up hanging around the elites in five-star hotels, first-class clubs for expatriate Westerners, and gated houses. I was overwhelmed by the progress of the country, which I never could have imagined in Germany. The circles in which I traveled were “Western”-oriented and liberal – and here, liberal meant alcohol, golf, and denim.

The other Pakistan was present, though, through the vitrine of the car window. Hassan Reza, a young architect, told me that life in Pakistan takes place in bubbles: you see the other classes, but there is no contact, no combination and – save for the odd act of charity – no interaction. No one mingles with the other. And that’s exactly what you feel: a strong ignorance of the other side and a palpable refusal to confront yourself with that ignorance.

You sense danger here in Pakistan, a danger of explosion from which you need protection. Soldiers everywhere guaranteed that no one from the upper classes would be affected by the poverty surrounding them. And I was safe, like them.

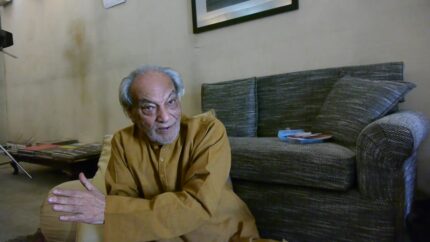

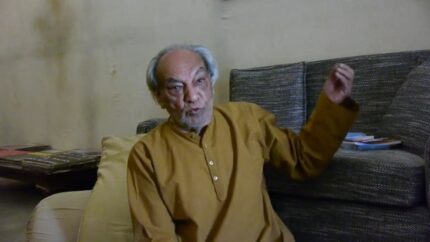

Yet my moment – the climax of my journey in Pakistan – was my unexpected encounter with the words of Reza Kazim, a lawyer, a philosopher, and a part-time intellectual prostitute. Select your toy of choice and click “www” if you want to share my experience, virtually: sanjannagar.wordpress.com/raza-kazim

His is a house in the heart of Lahore with dramatic stories to recount. I went there to visit the house more than to visit him. It was one of the few houses without a security gate. I walked up the stairs; around me were people at work. It looked like a music studio, lined with unusual speakers and sound equipment. An old man, with the bodily rhythm of a teenager, walked about with a cigarette in his hand. After a while, he was ready to be interviewed. Sitting on the floor beside the sofa, he talked about the “Hegelian” character of Islam, how he replaced Marxism with God, and, furthermore, why he left the communist party and started to “THINK.”

One cigarette followed the other. Reza Kazim offered me Lahore “water” (a glass of vodka), and mused on about the process of developing his philosophy and his revolution. His revolution, which he orchestrated out of his own tunes and notes in his institute, afforded him his own paradisiacal symphony:

Watch “Reza’s Revolution” (Clip I)

Watch “Reza’s Revolution” (Clip I)

I got his address from the only Jewish child ever born in Pakistan: Hazel, the daughter of two German Jewish refugees who moved to Lahore in 1937, looking both for safety and to serve the people as physicians. Hazel was born in an old house in Lahore. Despite being eminently popular in Lahore, Hazel’s parents had to leave the city forever due to the anti-Jewish sentiment in Pakistan caused by the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in the late 1960s. In 1972, Reza Kazim bought their house, just as the family was about to leave Pakistan. 40 years later, Hazel came back to Lahore from New York to rediscover her childhood and the house she grew up in. But more so than houses or memories, it was meeting Reza Kazim that reconnected her to Pakistan… Yet, I have to leave this story because it is the plot of another movie altogether.

“You look Isfahani,” Reza Kazim interjected in the middle of the interview. It just so happens that my parents are indeed from Isfahan; I realized, though, that Reza Kazim was trying to connect his philosophy with the old school of Isfahan. He figured I was there to construct a dialogue between Isfahan and Lahore. As a matter of fact, I never lived in Isfahan; and my life in Tehran is long-gone. I am not the traveller from Montesquieu’s “Persian Letters,” who, instead of visiting Paris, makes a left turn towards Lahore.

“If I would live in France, I would not fit in very well, because I would have a lot of work there – in the court of apparition! I can’t be worrying all the time about my bills. I would have no grievances against society; my grievances would be my personal career. Here I am free to have all my grievances against society. Because my standard of living is very flexible,” Reza Kazim explained. I understood. When I left Iran, I left it for more chances, more freedom, which I was no doubt afforded. But what did I use my freedom for? To pay bills and to fill out forms? I learned how to be part of the system instead of challenging it and being a pain. But, and I’m so sorry Reza, let’s change the subject…

Watch “Reza’s Revolution” (Clip II)

Watch “Reza’s Revolution” (Clip II)

Yes, that’s true! Even – or especially – as an artist, I often feel like an intellectual prostitute. You spend more time presenting your ideas than fulfilling them; presenting them in a way that the market will accept. Living in Germany, I learned very well how to present myself. I learned how to work not for myself or for my craft, but for the market. I feel like a prostitute of the world of capital, endlessly waiting for another grant to produce art, to think, to create.

Intellectual work today cannot be conceived without funding, Reza says. In our culture, they are synonyms: intellectual work IS the never-ending crusade for cash. So, as I see it, artists and intellectuals run about in a vicious cycle, since begging for funds is, simultaneously, the death of the artistic process. Creativity is mischievous; it does not adhere to deadlines. Forms and application documents are where ideas go to die. So what can we do without funding?

This is where my revolution begins: avoid applying for money. Nonsense! Someone has to pay the bills. So where else can I start my revolution? A revolution against what? And to what end?

My uncle received scholarships both from the Iranian and British governments to study in London. He continued to demonstrate, though, against everything that afforded him his elitist Western education: the Shah, imperialism, capitalism. To hide himself and his hypocrisy, he wore a mask when demonstrating on the streets of London – with varied success. At one demonstration, an Indian fellow greeted him by name. “How did you recognize me?” my uncle asked. “Change your jacket next time,” replied his Indian co-demonstrator.

I didn’t set out to write about revolution, its different theories, forms, or possibilities. Yet the necessity of revolution was an outfit I wore, a companion and a fellow traveler of mine in Pakistan. It can be a revolution to drink a glass of vodka in Lahore as you review the Iranian Revolution…

In fact, it was Reza Kazim’s words which lead me to revolution, to thoughts about Ayatollah Khomeini and the Iranian Revolution of 1979. Reza was in Iran as a lawyer at the time, mediating during the American hostage crisis. To my surprise, Reza supported the Revolution. Yet, his instincts gave him mixed signals about the Ayatollah: “I liked Khomeini for what he had done, but felt apprehensive about what he was going to do.” We discussed the harshness Ayatollah Khomeini had displayed ever since his victory. There is a form of harshness in Islam – a harshness against the self, not against the other. That is what I understood from Reza Kazim’s analyses. This harshness is like a dialogue with the self, causing an internal conflict with the inner words. Me and myself.

Words, words, words – what is the value of words and the self-critical reflection on their meanings? The Quran tells us that one minute of thought is more valuable than 70 years of prayer. Why then do people still choose 70 years of prayer? It is because thinking self-critically is to be harsh with the self. This is the harshness that Mohammad propagates. Even as an atheist artist, I can relate to the prophet’s call for being harsh on the self as a source of artistic creation. Harsh self-criticism is the prerequisite for creative miracles. Mohammad, who was illiterate, called his creation – the Quran – the final proof that he was God’s prophet.

For Reza, Pakistan never adhered to those words. That is why he created a laboratory – a kind of alternative revolution inside his institute. He involved the third world urban middle class – not by provoking them with the romanticism of riots, but by teaching them philosophy. Reza and his middle class disciples try to transcend thought, though, by putting their philosophical musings into scientific practice. Essentially, they read Hegel and then do research in physics. That is the core of his revolution: to resist a consumerist society, to find originality in the land of copies, and to work in philosophical peace with himself.

Watch “Reza’s Revolution” (Clip III)

Watch “Reza’s Revolution” (Clip III)

What I encountered in Pakistan was indeed a capitalist, liberal country. While you are there, you hear about the “free market” and the “land of opportunity” everywhere. Are they trying to be the US of the region? For me as an Iranian, it was unexpected to see how much freedom they have.

“I believed in that time that there was going to be a kind of competition between Hindus and Muslims on the matter of how to make better use of freedom. I hoped that we would make better use of freedom,” Reza said as he explained his reasons for moving to Pakistan after the partition of India and the independence of Pakistan in 1947. People like Reza believe that Pakistan hasn’t used its freedom, but has instead tried to establish a Western-oriented government. In fact, many Pakistanis see Iran as a paragon for Western, modern states of the region.

It often makes me angry when officials or mainstream media outlets in the West speak about Iran. What do they know about Iran? When I confront them, the answer is clear: they know Iran better than I do, because what matters to them is not reality, but the needs of the market. When I speak to “Iran experts,” I see a supermarket, in which Iran is being produced, recirculated, and reproduced. They consume the product they produced in the first place.

Now, as I walk in the streets of Lahore, I realize that I too am in a supermarket – producing and consuming Pakistan like the “Iran experts” do Iran. The lens of my camera is tinted with the preconceived notions I have packaged and brought to Pakistan. In fact, the supermarket goes both ways: Pakistanis, too, produce and consume me as a certain plastic image of Iran. Ironically, with Reza’s words of revolution still ringing in my ears, I am engaged in the free-market capitalism of clichés. Our perception of others – just like human rights, freedom of speech, democracy – are products, bandied about in the business of peace making.

There is a narrow line between the negative image of Iran in the West and the positive image of Iran in Pakistan. The narrow line is as dangerous as the “line of control” between Pakistan and India. The narrow line could also be a narrative thread of a theatrical evening. Oh yes, that was it: the reason I went to Pakistan in the first place! I keep losing track, shifting from Lahore to Isfahan, from Berlin to Tehran. When you meet five or six people a day, each with their own ideology and background, you are flooded with ideas. So I keep losing track and following new questions. Where and how can I be involved in a revolution? Nowhere and never?

There is no ideal answer, let alone an ideal solution to my questions. I don’t know Pakistan – and without that knowledge, I am powerless. This troubles me. The journey to Lahore has led me to an unexpected form of revolution – Reza’s revolution.

Reza puffs deeply at his cigarette, and you can see that he is at peace with himself. The electricity cuts out in the middle of our interview; he doesn’t have a generator. He doesn’t want to live like the upper class. Far from the gated houses, gated highways, gated people, there is a safe corner in which something is happening, men are at work. In practice, this could happen in Berlin as well.

The practical reason I went to Pakistan was to look for material to develop a theater performance – a performance, which could be relevant in Berlin.

Watch “Reza’s Revolution” (Clip IV)

Watch “Reza’s Revolution” (Clip IV)

What did Goebbels want to tell the Urdu-speaking Indians before the partition of Pakistan? I know what he said to the Iranians. Something like this: “Iranians and Germans share their Arian roots, so let them be united.” For many Iranians, their collective memory is – consciously or subconsciously – affected by the Persian language section of Radio Berlin and its propaganda. Goebbels found his audience in Iran.

As I enter the stage, I realize that I am in Berlin. The audience I had in Iran is no longer there. Nor are the people I met in Pakistan. What do I have in hand to offer my audience? How can I relate to them with the material I have brought? How can I show them pictures from far away, but simultaneously talk about the future of Berlin – about changes I witness every day in the city, changes that scare me? Did I travel to the future of Berlin? Is there anyone in the audience who agrees? Maybe I need to find my words and then find my stage.

Ayatollahs know far better than I how to speak to their worldwide audience, how to provoke and how to cause problems. I also want to cause problems – in a different way, certainly. When I think of Reza Kazim and the way he causes problems in his environment, I feel there are certainly alternative ways of being a problem case. “And we (Pakistan) are certainly a big problem case,” according to Reza Kazim. Each problem necessitates its own solution. What is that for Pakistan? And for my Berlin?

At the end of our meeting, Reza Kazim invited us to the first floor of his institute: a huge and beautiful living room. Pictures he took across Pakistan and the rest of the world hang on the walls. As is Pakistani custom, we were invited to eat together with his family and assistants. Before us a large table was filled with spicy yet delicious food. No wonder no one starves in Pakistan, despite the massive poverty. That is what I was told again and again: Pakistan knows no hunger, there exists an informal, sub-statist system of food distribution. But doesn’t Pakistan score devastatingly high on the World Hunger index? Who to believe – the NGOs or the Pakistanis I spoke to? There it is again, the supermarket of ideas and images. Which one should I buy?

Oh words, leave me alone for a bit. I want to eat…