One-on-one performance is a unique performance format in which each spectator encounters a single actor at a time. The performance is constructed as a series of individual encounters by the team of actors with a very specific time calculation to allow for a pre-designed rotation for every spectator. Earthport (an Egyptian/German collaboration created by MeetMimosa & Lamusica Independent Theater Group, and funded by Szenenwechsel) consisted of six scenes/performers receiving six spectators over the course of each performance. Every spectator received a clear itinerary describing the order of his/her one-on-one encounter. No two itineraries were the same, which meant that the spectators all had different journeys, different experiences and different narratives1.

One-on-one performance provides an individual and intimate experience of spectatorship, in which the spectator is involved in creating his/her own connections and meanings by linking the scenes he/she is experiencing. In this sense, the spectator plays an active part in building the performance via the action of reception/perception. The interpretation of every scene differs according to what precedes or follows it, and since each journey is different, we end up with six different constructions of narratives and emotional experiences within a single performance.

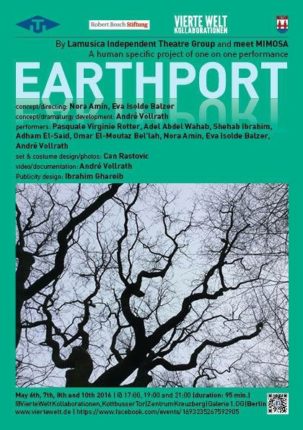

Photo: Nora Amin

Performed at Vierte Welt/Kottbusser Tor in Berlin in May 2016, Earthport built on the legacy of the Italian/Danish director Nullo Facchinni who created this format within a very clear methodology. Facchini’s method for “Human Specific Performance” intersects with interactive, biographical and sensorial performances, yet it adds much more to these forms that have experimented with all of the above, and re-shapes them into a particular and unique style. Co-directed by Eva Balzer and myself, after intense exchanges with Facchini in Denmark, Earthport carried the special signature of an “intercultural” performance, not only by interweaving the different cultures of the Egyptian/German cast, but by interweaving different performance cultures within the experiment while addressing the key issues of labeling the other and all the mental constructions that create prejudice and hierarchy towards a foreign identity.

Earthport provided a huge opportunity for creating a confrontational situation between the performer and the spectator. Since they came face to face in every scene, this was an ideal chance to test their connection and invite the spectator to examine her/his own responses towards the present otherness. The intimacy of the context only augments the challenge, as our actions are not reinforced by a large-scale esthetics, a distracting scenography or by the dynamics of a collective audience. The performer faces the spectator, witnessing the instant response and contribution of a stranger who suddenly discovers that he/she is co-creating an ongoing experience. On the one hand, it is the performer’s responsibility to suggest hospitality, create a safe space and display trust and self-confidence. On the other hand, it is also the performer’s mission to stipulate the professional borders, the implementation of the scene design and the spaces of exchange/interactivity.

Photo: Nora Amin

In spite of the potential freedom that exists within this format, and the general diversity of the spectator’s responses influencing each scene, the performance adheres to the pre-designed path resisting any instantly improvised situations except during emergencies. Each scene sticks to its specific duration, which equals the other parallel scenes so that all spectators exit their locations in unison, gather in a transit zone with one performer and enter new locations together. To respect this duration has been the greatest challenge, especially while giving room to the spectator’s freedom to respond. This challenge can only be met with experience, so that the performer can entirely appropriate the performative experience to the extent that s/he is able to expand some moments while intensifying others, and without losing track of mutuality and authenticity.

“Human Specific Performance” – as Facchini likes to call it – marks a space of intimate encounter that transgresses the usual borders of theater and performance together. It is a transgression of distance, due to the great proximity between the performer and the spectator. It is a transgression of codes, due to the gigantic shift in performative conventions across cultures. It is a transgression of the mental construction of “the other,” because it provides non-fictional accounts of biographical experiences. It is a transgression of fear, because it is a unique space where strangers meet and retrieve the possibility of brave vulnerability, of the human embrace – beyond categorization – and of love.

A trace that remains, empowers, heals and rewards.

Photo: Nora Amin

- Christel Weiler described her experience of the performance in her essay “The Art of Encounter”. Read it here on Textures: http://www.textures-platform.com/%3Fp=4571#footnote_2_4571. [↩]