Introduction

Good morning, and thank you for being here today. It was a great pleasure to be asked to speak at this symposium, and I have to admit, I was fairly surprised to be invited in the first place.

A few months ago, I attended a similar three-day symposium at the Goethe-Institut in London, mainly because I was intrigued by the title of the event: “Postmigrant Perspectives on European Theatre.” I was unfamiliar with the term “postmigrant,” and in all honesty, my first reaction was a vague sense of disapproval and discomfort towards the word. I maintain this same feeling today, and I hope my intervention will clarify why this is the case.

My name is Omar Elerian, and I am a third generation migrant. I was born in Italy to an Italian mother and a Palestinian father. My father was born in Egypt to Palestinian parents who fled Jaffa, now in Israel, in 1948. My mother was born in Gorgonzola, near Milan in the north of Italy. Her father had settled there, after leaving the central region of Umbria, to work as a carpenter, bringing his wife (my grandmother), who had migrated before him from even further south in Calabria. During my childhood, we continued to practice the family’s favourite pastime: moving homes and countries. We lived in Kuwait, Egypt, the United States, and a number of different places in Italy. One of the most vivid memories I have of that time is my brother and I waiting to open the two gigantic steel trunks that moved with us around the world. They held our most treasured toys, books, clothes, and at least 25 sets of duvets and bed sheets, which my mother was never willing to leave behind. Today, those trunks are still taking up most of the space in my parent’s cellar. I have no idea what they contain anymore, and my parents haven’t moved in the last 20 years; but I suspect my mother might still have a spare set of blankets in there, just in case.

At the age of 23, I moved from Milan to Paris to pursue my study of theatre. In 2009, I moved from Paris to London, following my ambitions to confront a different theatre culture. I am now 35 years old, and the one thing I’ve learnt so far is: “there’s no such place as home.”

Home, in my experience, has always been a state of mind.

This is very practical, since I don’t need two giant steel trunks to carry it with me.

I like defining myself as a migrant, and I am blessed to have (had) the luxury to be able to travel and work freely across Europe, thanks to my Italian passport. I love being able to define my identity every day – a layering of experiences and encounters, decisions and inputs, actions and reactions. Who I am is what I make of myself.

But.

Who am I in the eyes of others?

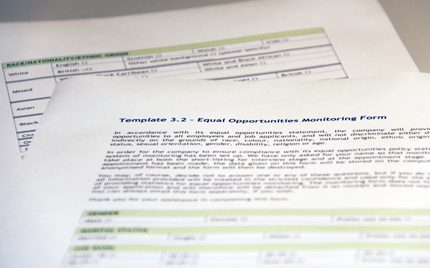

This is an Equal Opportunities Monitoring Form. You have to fill out one of these for almost anything official or work-related in the UK. I’ve always had problems with these forms, mainly because I never find a box to tick for myself.

Just a couple of years ago, though, my freedom to define my identity was indelibly violated in Tel Aviv airport. Entering Israel for the first time in my life, I walked up to the immigration officer and handed over my Italian passport. He opened it and read my name. He then asked me for my father’s name, to which I answered: “Mostafa.” Next he asked for my grandfather’s name: “Eissa.” By the time I had finished pronouncing his name, my passport was withheld, set to the side, and another officer quickly escorted me to a waiting room in the arrivals area. The rest of the theatre company made it through Israeli immigration, except for two colleagues: Gabeen Khan and Nazanin Armin. Their ancestors’ names had succeeded in identifying them more prominently than their British passports and their laid back East Londoner looks. We were held in the waiting room for 4 hours, asked to repeat our family genealogies every hour, and were forced to accept parts in a play for which we didn’t – and never would – study. Who and what I thought I was became irrelevant in this context. I was the “other,” the enemy, the uninvited. And there was nothing I could say or do to contradict that.