Over the weekend (13-14 May 2017) I saw Théâtre du Soleil’s latest production, Une chambre en Inde (A Room in India), on the invitation of its director, Ariane Mnouchkine, enjoying the hospitality of her and her entire crew. The production premiered in November 2016 and was inspired, among other things, by the South Indian (Tamil language) Kattaikkuttu or Terukkuttu theatre (the latter name being preferred by the ensemble and often abbreviated to Kuttu). Une chambre en Inde is a true spectacle of “total theatre” as you do not see it so often anymore — a spectacle that is alive, where the actors sing, move and act themselves; a spectacle that asks many questions about the world and its often violent fragmentation. A spectacle that is thoroughly entertaining for all its four hours, funny, demanding introspection and, in the end, proposing a solution that gives hope but is too idealistic.

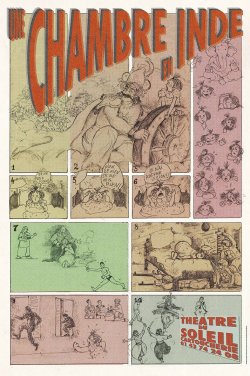

Image ©Théâtre du Soleil

Hats off for the entire crew and its director for having brought this collaborative work on the stage. Lots and lots of research, discussion, disagreements, passion, despair and surprise must have gone into it and all that is visible, audible and palpable. The mis-en-scene, costumes and props — the aesthetics — are a joy to watch. And so is the music by Jean-Jacques Lemetre — with one or two take-aways for our own Kattaikkuttu ensembles: the music really underplayed and supported the singing of the onstage actors rather than being on top of them; and the support of the entire crew as pinnani (chorus) was simply fantastic and enhanced the entire production. The effort on the part of the performers to act the Terukkuttu scenes in a language (Tamil) none of them spoke and to approach an original as closely as possible is almost unimaginable.

Une chambre en Inde is about the role of theatre and a theatre director’s struggle with inspiration (if inspiration is still something other than hard work…) — seeking advice from other famous theatre directors with Shakespeare and Tchekhov appearing live on the stage. It is about terrorism in its manifold and complex manifestations (quite a bit of extremist-Islam bashing, but also references to local manifestations of BJP “Hindu fundamentalism”). Watching the play I realized how deep France’s trauma goes after the terrorist attacks — something we do not get to feel in South India; a trauma that must be all the bigger, deeper and more complicated when it involves an international cast of performers many of whom come from countries that are partners in the crime of terrorism. It takes guts to embark on such issues and have them on the stage to be viewed (and disrupted) by anyone who would see it fit to do so.

Une chambre en Inde is about the status of women also, anywhere and including Draupadi and Ponnuruvi (Karna’s wife), about arranged marriages in India, and about Saudi Arabian women being banished from driving a car — and a bicycle. And finally it is about our role as human beings in the unfolding of all this.

Une chambre en Inde tackles an array of complex issues that are, as so often is the case, interlinked to Europe’s own historical role as a colonizer and to capitalism protecting what is at stake for those whose interests transcend the boundaries of nation states. Complex issues that can only be viewed from many different angles — angles that will change depending on where you come from and what is at stake for you…. To my taste this complexity was not always covered and some things came across a bit flat and simplistic, but that may also have been because my French is not up to the mark to understand all tongue in cheek comments.

Coming back to the Terukkuttu scenes, I was able to look at these only from an entirely subjective point of view being so used to Rajagopal’s1 different style of performance. The multicultural cast of performers involved in these scenes had been trained by Kalaimani Purisai Kannappa Sambandan Thambiran and M. Palani and, therefore, featured their (Purisai) style of Terukkuttu with which I am less familiar. The entire performance is as close as possible to a real Kuttu performance — the actors sing and speak in Tamil, there’s a Kuttu melam (orchestra) in the background that brings you almost beautifully grotesque excerpts from Draupadi’s Disrobing and Karna’s Death, which are situated as productions within the production.

I am still in the process of digesting the position and role of Kuttu in Une chambre en Inde. What exactly motivated the idea of reproducing authentic Terukkuttu? When I asked Ariane, she said that for her Terukkuttu is the mother of all theatres, a kind of ur-theatre. Seeing it she was so carried away by its power and vitality that it rekindled her idea of what theatre is and could or should do. Terukkuttu does not question the role of theatre in the world. It just is or does — unquestioningly…. Kuttu as the solution to all other theatres that are dead or dying…?

The Kuttu scenes were quite separate and isolated in the entire spectacle, dramatized as dreams or visions of something else — aborted every time when the phone rang and the Kuttu ensemble would hurry off the stage taking all their belongings with them. The Kuttu performers did not grab the phone to answer it, nor did they try silencing it for their performance to continue. In a way they were (left) outside the discourse — exoticized? — whereas this may not have been the intention of the director.

What happens to a theatre form when it gets transplanted into another cultural context? What happens to the interpretation of Kuttu’s Mahabharata texts? What happens to its music and movement? What happens to its raw power? In spite of the great efforts taken to study the form and train the performers, a certain classicization of the women’s voices (Draupadi and Ponnuruvi), in particular, seems to have taken place. As a notorious Kuttu rasikar (fan) and being used to Rajagopal’s style and way of singing, I missed the high pitch and the high-paced, sharply timed movements using space and coinciding with the mridagam’s tirmanams (rhythmical endings), the quality of voice, that typical Kuttu sound and timbre, and its “rawness” in the middle of the night, echoed by the harrowing melodic accompaniment of the mukavinai (oboe-like high pitched instrument). The Kattiyakkaran (Clown acted by different performers) was not alert enough, too slow to be at the back and call of the King. He did not really bring in laughter, in spite of the fact that there was a considerably amount of comedy in the rest of the production. I missed the casual interaction between the Kuttu performers and their spectators (and, in the production, between them and their said rasikars with whom they never interact…).

©HannedeBruin/Kattaikkuttu

- P. Rajagopal is a Kattaikkuttu actor, director and playwright, co-founder of the Kattaikkuttu Gurukulam and Hanne’s husband. For further information, please see the end of this article. [↩]